The Wife of Bath's Prologue on CD-ROM (1996): Editor's Introduction

Peter Robinson (De Montfort University, Leicester)

- General Introduction

- The Wife of Bath's Prologue and The Canterbury Tales Project

- The Canterbury Tales Project: its predecessors and its history

- The aims of The Canterbury Tales Project and this CD-ROM

- The making of this CD-ROM

- Acknowledgements

1. General Introduction

The Wife of Bath is one of Chaucer's most vivid creations, and one of the great characters of all literature. There are fictional personalities who appear to have a life beyond the words their creators give them: such are Chaucer's Wife of Bath and Pardoner, Shakespeare's Falstaff and Hamlet, certain of Dickens' characters. We think of them as we would think of living or historical persons; we bring to them our own concerns; our debates about them become debates about ourselves. To read the surveys of scholarship on the Wife of Bath (in, for example, Andrew's summary in the Variorum Chaucer) is to read our own intellectual history, through Marxism, Christian exegetics, feminism, and deconstruction.

Yet, though these characters may become creatures of our imagination, they can only commence life through the words their authors give them. In the case of the Wife of Bath, the words themselves are in question. Depending on which manuscript you read, you may meet a very different Wife of Bath. This is shown most dramatically in the opposition between the two manuscripts usually considered most authoritative for the text of the Canterbury Tales, the Hengwrt and Ellesmere manuscripts. In the Wife of Bath's Prologue, Ellesmere has twenty-six lines which are not present in Hengwrt: lines 575-584, 609-12, 619-26, 717-20 in the numbering of the most widely-used modern edition, the Riverside Chaucer. Included in these are the following (622-26), where the Wife appears to give the clearest possible indication of her voracious and indiscriminate sexual appetite:

| I ne loved neuere by no discrecioun But euere folwed myn appetit Al were he short or long or blak or whit I took no kepe so that he liked me How poore he was ne eek of what degree |

| For sothe I wol nat kepe me chast in al |

|

For sith I wol nat kepe me chaast in al Whan myn housbonde is fro the world agon Som cristen man shal wedde me anon |

One will look in vain in Hengwrt for any passage which suggests, as do these lines in Ellesmere, that the Wife is a "monster of carnality" (D.W. Robertson). There is no such passage in Hengwrt. Hengwrt's Wife is arguably a more subtle, more satisfyingly rounded portrait than is Ellesmere's: she is still outrageous, but with hankerings after respectability, and certainly a character better suited to the romance Chaucer puts in her mouth. In addition, there are a host of differences of wording, presentation, and (especially) metre between the two manuscripts. Even without the dramatic differences of the twenty-six lines, these smaller differences are cumulatively sufficient to make reading Chaucer in Ellesmere a very different experience from reading him in Hengwrt.

2. The Wife of Bath's Prologue and The Canterbury Tales Project

The dispute as to which manuscript of the Canterbury Tales we should read goes to the heart of the question of how we should read Chaucer. It affects our sense of his poetry, of his narrative art and characterization, and of the unity of the whole. I have so far mentioned just the two best-known manuscripts, Ellesmere and Hengwrt. But it is not simply a matter of comparing these two manuscripts, which are neither direct copies of one another nor of a single common exemplar. In total, there are eighty-eight fifteenth-century witnesses, around sixty of them relatively complete, to the text of the Canterbury Tales. For the Wife of Bath's Prologue, there are fifty-eight witnesses. Any one of these might contain vital clues as to the history of the text. Some certainly do: Christ Church 153, for example, was written some half a century after Hengwrt, has a text very close to that of Hengwrt, but intriguingly includes all the lines found in Ellesmere. At line 117 of the Wife of Bath's Prologue, three late manuscripts otherwise of apparently little distinction all read "wright" for "wight", a reading Talbot Donaldson argues was in Chaucer's original: but if so, how did "wright" come to these manuscripts and to no others?

To discover the history of the text, even for just the earliest manuscripts, one must therefore look at every witness. In theory, one might not wish to stop at 1500, as we have chosen to do; but one must stop somewhere. Nor is it possible to settle the question just for one part of the Canterbury Tales, in isolation from the rest. Scribes copied long works such as this in sections; an account of textual relations which is true for one section may be quite false for another. There is no help for it then. To settle, as well as one can, what Chaucer is most likely to have written for any one word in any one part of the Canterbury Tales one must look at every word in every one of these eighty-eight witnesses to the text.

3. The Canterbury Tales Project: its predecessors and its history

The Canterbury Tales Project is not the first attempt at a solution to these problems. Koch, a century ago, examined all the textual evidence in all the manuscripts of the Pardoner's Prologue and Tale. The most elaborate effort is that of John Manly and Edith Rickert, who gathered copies of all the witnesses and collated them all, word by word, and then sought to arrive at a single text on the basis of their analysis of the witness relations emergent from the patterns of agreements they found in this collation. The result was the monumental eight volumes of their The Text of the Canterbury Tales. However, they worked under conditions of great difficulty (Rickert died before it was finished, and Manly was ill in the latter stages); no later editor has accepted their text; the presentation of their conclusions is so obscure that it is difficult to determine how far they achieved their stated aim, of uncovering the textual relations of all the witnesses. It is clear that they left vital questions unanswered. The system of 'constant groups' of witnesses they devised actually accounts for only a third of the extant witnesses, and tells us nothing about the relations of the most important and earliest manuscripts - including Hengwrt and Ellesmere.

It is arguable that the reason for Manly and Rickert's failure was that they were simply overwhelmed by the immense amount of evidence they gathered. Their collation required some 60,000 collation cards, each containing information on the readings in some eighty witnesses: upwards of five million pieces of information in all. This vast weight of information was simply beyond their manual methods of analysis. In addition, the printed record of their collation, in volumes five to eight of their edition, is impenetrable, to the extent that it is very difficult to reconstruct from this the actual reading of any line in any witness.

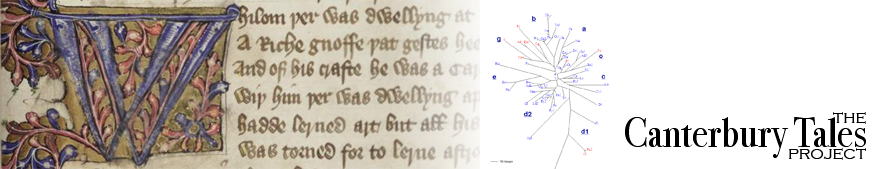

The advent of the computer, and its application to textual editing, offers ways past the difficulties both of analysis of so much material and of its presentation in an accessible manner Computers thrive on the sorting, organization, and presentation of just such vast collections of data as this. Advanced systems of computer analysis offer the promise of finding the patterns of textual relations implicit in the massive quantity of information concerning witness agreements and disagreements generated by collation. The technique of cladistic analysis, developed in the last thirty years by evolutionary biologists to construct trees of descent from information of the shared characteristics of species, has given particularly promising results. Further, the revolution in electronic publishing now makes it possible to present, at moderate cost on a single CD-ROM disc, vast quantities of information in an accessible manner.

It was with these two factors in mind - the possibilities of computer analysis and computer publication - that in 1989 I applied for, and was granted, funding from the Leverhulme Trust for transcription of the manuscripts of the Wife of Bath's Prologue into machine-readable form. At first, this was intended only as a modest experiment, to test techniques of transcription, collation and analysis which I was then developing. Four events in the following years converted this experiment into the full Canterbury Tales Project, of which this CD-ROM is the first major publication.

The first event was Elizabeth Solopova coming to work on the transcription, in December 1991. In the following eighteen months, she and I developed the guidelines for transcription for the witnesses of the Wife of Bath's Prologue which is now the cornerstone of the entire Canterbury Tales Project. These guidelines are printed in the first volume of the Project's Occasional Papers series, and are also provided on the CD-ROM. More important still than this: in this period we satisfied ourselves that such a transcription could be indeed done, and that it would create a valuable scholarly resource. Further, without her remarkable feel for the text and its scribes, combined with her unfailing care for detail over this long period (and, especially, in the final frenetic weeks before publication), the work underlying this CD-ROM simply could not have been done.

The second event was our joining forces with Norman Blake, in June 1992. By then, Elizabeth Solopova and I were certain that we could do something useful with the Wife of Bath's Prologue. From a lifetime's experience of editing Middle English texts (and, especially, Chaucer) Professor Blake was confident, as we could not be, that what we proposed might do something useful for the whole of the Canterbury Tales. Together, we decided to seek ways to make this happen. At the time of writing (February 1996), the Project has grown to some ten staff and associates, part-time, student and other, in three countries, with centres in Sheffield, Oxford, and Provo, Utah. Together, we have now transcribed some fifteen percent of all the text of all the witnesses, and have funding in place to double this over the next three years. The great respect Norman Blake has earned in the scholarly community and his judicious diplomacy have been instrumental in this growth while his example and experience as an editor have guided this Project throughout.

The third event (which is actually more like a continuing process) was the work of the Text Encoding Initiative, under its editors Michael Sperberg-McQueen and Lou Burnard, in developing a system of encoding of machine-readable scholarly texts. I was closely involved in this work, as chair of the Textual Criticism workgroup from 1992 to 1995 and as a member of the Primary Text Transcription workgroup over the same period. Without the implementation of Standard Generalized Markup Language (SGML) developed by the TEI, again this CD-ROM simply could not have happened - or could have happened only in an unsatisfactory and etiolated form.

The fourth event was the agreement of Cambridge University Press, in November 1992, to act as our publisher. The devotion of the Press to this Project has been exemplary. It is not only Kevin Taylor and Andrew Brown who have nurtured this publication: every one of the many people I have met at the Press appears to have a personal interest in the Project. Again, without the willingness of the Press to experiment, to commit considerable resources without any certainty of success, this CD-ROM could not have happened.

4. The aims of The Canterbury Tales Project and this CD-ROM

When Norman Blake and I first met we had a single aim: to use the computer methods now available to us to determine as thoroughly as we could the textual history of the Canterbury Tales. Here, we face an apparent impasse. We can make no firm judgements about the textual relations of any witnesses, for any part of the Tales, until we have transcribed, collated, and analyzed every word in every witness of every part of the whole text.

This remains our long term aim. However, we have developed two other aims, capable of immediate realization. The first of these aims is that we should publish, as soon as we could, all the materials of transcription, collation, and description upon which our final analysis would be based. Thus, this CD-ROM contains our transcription of all fifty-eight fifteenth-century witnesses to the Wife of Bath's Prologue. It also contains our word-by-word collation of all these witnesses, digital images of every one of the 1200 pages (manuscript and early printed edition) we have transcribed, transcriptions of the glosses (by Stephen Partridge), descriptions of each witness (by Dan Mosser), and spelling databases grouping every occurrence of every spelling of every word in every witness by lemma and grammatical category. We might have chosen just to publish our transcriptions. Instead, we wish to make it possible for other scholars to have access to all the material we have gathered. The difference between the two decisions may be simply measured: the transcriptions of the witnesses alone consumes around 3 megabytes. The collations, spelling databases and all the other textual materials on the CD-ROM (excluding the images) consume 156 megabytes.

Our second aim is to present all this material in as attractive and accessible a fashion as possible. This CD-ROM contains around ten million items of information: about individual words in particular witnesses; their part of speech; what other witnesses have at this point; etc. Nor did we have any precedent to guide us: so far as I know, this is the first time anyone has tried to present so great a mass of information of this kind about a whole textual tradition in electronic form (indeed, in any form). We sought a manner of presentation which would make all this material available to the reader, without overwhelming him or her. The technique we chose was hypertext. At first, we have the reader see an apparently straight-forward, plain and single text. This is 'the base text for collation' which the reader sees on opening the electronic book: essentially, a very lightly edited representation of the Hengwrt manuscript text. But through hypertext, we would make this single text the starting point of exploration. Thus: to click on any line number in this base text will show the reader information about just which of the fifty-eight witnesses have this line, and where they have it. To click on any word in this base text brings up a window containing a complete record of all the readings in all the witnesses at that word. Further mouse clicks lead to the transcription of each witness, to images of the pages, to the transcription of the glosses, to and from the witness descriptions and the transcription introductions, and into and out of the spelling databases for each witness and for all the witnesses together. Altogether, some two million hypertext links tie together all the information on the CD-ROM. If we have a precedent, it is the elaborate medieval manuscripts of the Glossa Ordinaria, where the single text in the centre of the page is surrounded by a complex web of inter-relating apparatus and commentary.

In the process of preparing this CD-ROM, our first aim (to uncover the history of the text) has seemed ever more remote, and the second and third aims (of publication, in the most accessible possible form) and seemed ever more pressing. Accordingly, there is no discussion whatever on this CD-ROM of the textual relations of the witnesses. This is not because we have not already formed opinions, and our decision to constitute our base text on the Hengwrt manuscript suggests where we currently stand in the debate over the relative merits of the two best-known manuscripts. Articles by Elizabeth Solopova and myself in the second volume of the Occasional Papers present what we have discovered so far. However, these articles are working hypotheses, which must be tested on the far wider range of material which the Project is making available. It is not appropriate, therefore, to include them on this CD-ROM, which contains (as it were) the 'hard' data on which further discussion must be based.

5. The making of this CD-ROM

The core of this CD-ROM is the transcription of the fifty-eight witnesses. Each transcript has been checked at least once by both Elizabeth Solopova and myself, and most have been checked twice by both of us. In addition, each transcript has been checked by at least two other people. Our aim was not to eliminate error entirely, but to reduce it to a level at which scholars could feel confident in their use of the transcripts. An error rate of one error every 4000 characters, or about one every hundred lines, should achieve this. Further, the great majority of such errors should be matters of spelling, and should not alter the substantive reading of the witness. All first transcripts and most subsequent checks were done from copies derived from microfilm. Where we could, we did the final check of each transcript against the original: thus for all manuscripts in Oxford and Cambridge and in the British Library.

This CD-ROM contains two word-by-word collations of the witnesses: a 'regularized spelling' and an 'unregularized spelling' collation. These collations were done by the program Collate, developed by me with the assistance of funding from the Leverhulme Trust from 1989. As part of the collation process, Collate and associated purpose-written programs also created all the spelling databases on this CD-ROM and made all the hypertext links between the collations, transcripts and spelling databases: around 1.9 million hypertext links. The final collations with Collate were done by Elizabeth Solopova and myself in December 1995 and January 1996, with the spelling databases generated from these collations. Finally, this material was linked to Stephen Partridge's transcriptions of the glosses, to Dan Mosser's descriptions of the witnesses, to Marina Robinson's digitized images of the witness pages, and other matter, to create the final CD-ROM.

6. Acknowledgements

A task of this scope is far beyond the ability of any one person, and I have already mentioned many without whom this work could not have been done. Many others, not yet mentioned, have contributed to the completion of this CD-ROM. Marilyn Deegan has throughout offered encouragement and practical help. Susan Hockey was my first project director, and has remained interested in this work throughout. Most of the work for this CD-ROM was done while I was based in Oxford University Computing Services, and I thank its directors, Alan Robiette and Alex Reid, and administrator, Keith Moulden, for their understanding and support. Anne Hudson has been a strength at critical times, and an example at every moment. In common with every student of Middle English manuscripts this generation, I owe much to the learning and generosity of Malcolm Parkes and Ian Doyle. I have profited from discussions on textual encoding and critical editing with many people over the six years of this work: I am sensible particularly of how much I have learnt from Robin Cover, Hoyt Duggan, Paul Eggert, Malcolm Godden, Robert O'Hara, Prue James, Ian Lancashire, Kari Anne Rand Schmidt, Peter Shillingsburg, Eric Stanley, Toshiyuki Takamiya, and Ron Waldron. I am grateful to Jill Havens, James McCabe, Hubert Stadler, Cathy Swires, Paul and Maureen Watry, Laura Wright, and Diana Wyatt for the help they gave in the early stages of the transcription. The staff, students and associates of The Canterbury Tales Project have given both good cheer and practical help in the last three years: I thank Linda Cross, Simon Horobin, Beverley Kennedy, DarIn Merril, Michael Pidd, Estelle Stubbs, Paul Thomas, and Claire Thomson. Especially, I thank Michael Pidd and Estelle Stubbs for checking our transcripts of all the witnesses, and also carrying out a further check of our transcripts of the Cambridge manuscripts against the originals.

I have benefited from the generosity of the staff of the many libraries and archives I have visited or otherwise contacted. Bruce Barker-Benfield of the Bodleian Library unravelled the mysteries of manuscript nomenclature for me. In Oxford, David Cooper of Corpus Christi College and Richard Hamer of Christ Church have been most helpful; in London, Andrew Prescott and Michelle Brown of the British Library have both entertained and enlightened me; in Cambridge I am grateful to David McKitterick of Trinity College and to the staff of University Library and the Fitzwilliam Museum. Elsewhere, the staff of the Firestone Library Princeton, the Pierpont Morgan Library New York, the University of Chicago Library, and of the Bibliothèque Nationale Paris have been most obliging.

I must acknowledge once more the debt I owe to the people listed on the title page above, and to whom I have referred in the account of the making of this work: to Norman Blake, Andrew Brown, Lou Burnard, Dan Mosser, Stephen Partridge, Marina Robinson, Elizabeth Solopova, Michael Sperberg-McQueen, and Kevin Taylor. It is not otiose to thank them formally once more; thanks can not be repeated too often for their help. One should not single out one person: but the frequency with which Elizabeth Solopova's name occurs in this introduction does only the barest justice to her immense contribution. It is conventional to claim the merits for others, and the failings for oneself. For me, after all this help from so many, what might be convention is truly heart-felt.

Finally, the greatest debt is to my wife, Valerie, and to my family. Support is most valued when it is most needed. No words can repay their understanding of what must often have seemed a mysterious obsession, and their support through the most difficult times.