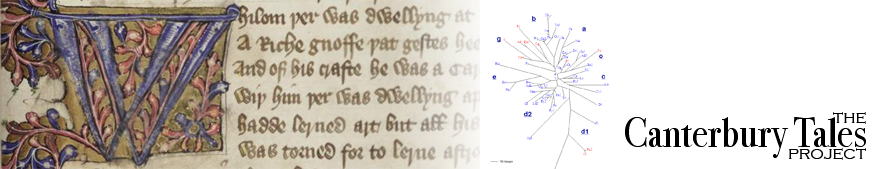

The Hengwrt Chaucer Digital Facsimile (2000): The Language of the Hengwrt Chaucer

Simon Horobin (University of Glasgow)

1. Introduction

The Hengwrt manuscript was copied in a variety of Middle English [ME] current in London at the end of the fourteenth and beginning of the fifteenth century. Before examining the language of this manuscript in detail, it will be useful to consider the development of London English during this period more generally.

2. The Development of London English

The Late Middle English period is characterised by the huge degree of dialectal variation which is reflected in the written record. Chaucer himself drew attention to this in Troilus and Criseyde (V 1793-4):

And for ther is so gret diversite

In Englissh and in writyng of oure tonge

The extent of this written variation may be exemplified by a consideration of the large number of different spellings of the common word SUCH recorded by the Linguistic Atlas of Late Mediaeval English [LALME]. While many of these spellings are relatively straightforward, for example swich, swech, soch, sych, others are less obviously recognisable to the modern reader, eg. schch, slkyke, sik, sqwych, zueche. During the second half of the fourteenth century the functions of the vernacular changed and English began to be used as the language of government and administration, and for literary purposes. As a result of the general elaboration of English there was an increased need for a standardised written variety of Middle English which could be understood over a wide geographical area.

The initial emergence of a standard written language can be dated to the fourteenth century, although the process was ongoing throughout the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. M.L. Samuels (1963) first distinguished four ‘types’ of written standards in texts copied during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, which he labelled types I-IV. Type I, also known as the Central Midlands Standard, is found in a number of texts associated with, although not exclusively, John Wycliffe and the Lollard movement. This language is found in a large number of manuscripts of religious texts and Bible translations produced by the Lollards, copied and circulated widely throughout the country. The language is based on the Central Midlands dialects, particularly counties such as Northamptonshire, Huntingdonshire and Bedfordshire, which were centres of Lollard activity. Type I enjoyed a wider currency than any other type until 1430, and seems to have functioned as a kind of ‘literary standard’ during this period. Type II is found in a number of manuscripts copied in London in the mid fourteenth century, such as the Auchinleck manuscript. The Auchinleck manuscript is a large collection of ME Romances copied by a number of scribes, produced in London probably for a member of the monarchy. However despite these royal and literary associations there is no evidence that this language was regarded as a prestigious standard, it was simply the variety of London English which replaced the earlier Essex-based language, as represented by the Proclamation of Henry III of 1258. Type II differs from the earlier usage in that it shows a marked influence of forms from the East Anglian dialects, a result of large-scale immigration into London from those counties in the mid fourteenth century. Type III is the language of the capital in the late fourteenth century, recorded in the earliest Chaucer manuscripts and the Hoccleve holographs. This language differs from Type II in showing the influence of the Midlands counties, reflecting different immigration patterns later in the fourteenth century. Type IV, also known as Chancery Standard, was used by the clerks employed in the various offices of the Medieval administration from about 1430, and it is this language that formed the basis of our Present-Day written standard. This language shows the influence of further waves of immigration from the Central Midlands counties, with a number of linguistic features filtered down from the Northern dialects.

The language of the Hg manuscript therefore belongs to the standardised variety of London English known as Type III. It is important to emphasise that Samuels’ types do not show the same degree of uniformity as does Present-Day standard written English. In considering the development of standard written English J.J. Smith has stressed the difference between ‘fixed’ and ‘focused’ standard languages (Smith 1996, 63-78). Present-Day standard written English is a ‘fixed’ standard as it consists of a fixed set of rules from which no deviation is permitted. Types I-IV were ‘focused’ standards as they incorporated a degree of internal variation. Smith has drawn a helpful parallel between Types I-IV and the Present-Day spoken standard, or reference accent, known as Received Pronunciation [RP]. While many speakers of English use RP few of these are likely to show all the features characteristic of this accent. RP is therefore an abstract set of prototypical features to which speakers tend, rather than a fixed set of linguistic shibboleths from which any deviation is stigmatised.

If we examine the evidence for Type III in greater detail we may identify the kind of variation found within this standardised variety of ME. In his article Samuels listed a number of features as characteristic of Type III, including the following: though THOUGH, nat NOT, swich SUCH, bot BUT, hir(e) THEIR, thurgh THROUGH. While these forms appear regularly in Type III texts they are not the sole spellings adopted for these items. For instance the Hg manuscript has both nat and noght as spellings of NOT and these seem to be used in free variation. Similarly there are two dominant forms of the item THOUGH in Hg, thogh and though, and both seem to have been equally acceptable. In fact there is a third form theigh not recorded by Samuels which appears in just 7 occurrences in Hg. For the purposes of localisation LALME merged the Hg and El manuscripts into a single linguistic profile. However to treat these two manuscripts as evidence for a single variety of ME ignores a degree of important variation between the two manuscripts. For instance while the two spelllings thogh and though are both found in El, the Hg spelling theigh is not used in El.[1] Comparison of the language of Hg and El with other Type III manuscripts reveals further evidence of the variation permitted within this variety. For example both Hg and El employ the spellings nat, noght for the item NOT. The same forms are also found regularly in the holograph manuscripts of Thomas Hoccleve, although Hoccleve also uses a third form naght not recorded in the Hg and El manuscripts.[2] Such variation warns us against viewing these types of London English as discrete and unrelated developments. For instance the spelling theigh recorded in the Hg manuscript is in fact characteristic of Type II, and is the regular form of the main hand in the Auchinleck manuscript. Another manuscript copied in Type III, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge MS 61, a copy of Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde, also contains seven occurrences of this spelling alongside the more common Type III forms. Therefore we must view Samuels’ typology as a linguistic continuum rather than as a series of discrete linguistic varieties.

The publication of the full electronic text and facsimile of the Hg manuscript allows us to take into account all the forms recorded throughout the text in its entirety. By drawing upon these resources it is possible to examine the variation between spelling forms for certain items in greater detail than has previously been possible. This provides important new possibilities for a reconsideration of the evidence that the Hg manuscript offers for a reconstruction of Chaucer’s own spelling habits. This will be the subject of the next section.

3. Evidence for Chaucer’s spelling

Following the work of Doyle and Parkes (1978) and Samuels (1988b) it has been established that the Hg and El manuscripts of the Canterbury Tales were copied by the same scribe. This scribe, known as Scribe B, has also been identified at work in Trinity College, Cambridge R.3.2, a copy of Gower’s Confessio Amantis, and the Cecil Fragment of Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde. These identifications have encouraged scholars to attempt to draw upon the evidence of these manuscripts in order to distinguish orthographic forms which derive from Chaucer’s own spelling habits. These attempts have drawn upon the identification of the language of the Fairfax and Stafford manuscripts of Gower’s Confessio Amantis as the poet’s own usage.[3] By comparing the orthographic features of his stint on the Trinity copy of the Confessio Amantis with the authentic Gowerian forms of the Fairfax and Stafford manuscripts, Samuels (1988) argued that Scribe B consistently translated the archetypal forms of Confessio Amantis into his own preferred spelling system. This same copying practice has then been assumed for his work on the Chaucer manuscripts, and forms common to Hg and El only are argued to be due to constrained selection.[4] These forms are thus preserved from the exemplar and, given the textual authority of these manuscripts, ultimately from the archetype, and are therefore argued to be Chaucerian. Using this method Samuels compared the spellings of four words in the Fairfax and Trinity Gowers and the Hg and El Chaucers, identifying the following spellings, unique to both Hg and El, as authorial: agayn(s)/ageyn(s), biforn/bifore, wirke (vb.), say/saw. The acceptance of these forms as authorial is thus based on a string of hypotheses that assume a straightforward textual history. While the claim that Fairfax and Stafford are linguistic autographs may be authoritative, we can be less sure that they represent the immediate exemplar of the Trinity Gower. Any intermediary copy between the Gowerian archetype and the Trinity manuscript could transform the authorial language, and alterations in the frequency and distribution of authorial forms would be inevitable. The assumption that a scribe consistently translated the language of his copytext can only be proven by comparison with an immediate exemplar, and as this does not apply to Scribe B it is safest to assume that he was more likely to have mixed the forms of his exemplar with his own preferred forms. Rather than relying on the evidence of the Trinity Gower to determine Scribe B’s copying practice for his work on Chaucer, we must turn to the Hg and El manuscripts themselves, where the evidence reveals the problem to be less straightforward than Samuels suggested.

By drawing upon the electronic texts of Hg and El it is now possible to consider the evidence presented by these forms across the entire manuscripts. In the following table I give the figures for all the spellings of the forms Samuels cited as authorial on the basis of constrained selection, across the entire text of both witnesses.

| Hengwrt | Ellesmere | ||

| again(st) | again(s,st) | 1 | 3 |

| agayn(e,es) | 123 | 143 | |

| ageyn(s) | 16 | 20 | |

| ayein(s) | 9 | 20 | |

| ayeyn(s,es) | 0 | 11 | |

| before | tofor- | 0 | 1 |

| b-for- | 80 | 87 | |

| work(vb.) | werk- | 19 | 29 |

| wirk- | 1 | 0 | |

| werch- | 7 | 7 | |

| wirch- | 8 | 5 | |

| saw | saugh(e) | 31 | 113 |

| saw(e) | 47 | 9 | |

| say(e) | 45 | 8 | |

| seigh | 13 | 3 | |

| sey(en) | 3 | 0 | |

| sy(e,en) | 0 | 6 |

The distribution of forms across the two manuscripts certainly calls into question Samuels’ conclusions, as one could support claims for the authority of quite different forms. For example, a hypothesis that Scribe B consistently translated his exemplar into his own spelling system would mean that the forms ayeyn/ayein and tofor- could be relicts and therefore possibly archetypal. Similarly, if it was assumed that the scribe was meticulously preserving the spellings of his copytext, these minor forms could be understood as the result of the unconscious use of his own spelling system. The number of different spellings for work and saw testify to a range of variant forms, making such analysis complicated and highly subjective.

In a situation of this kind, where immediate exemplar and type of copyist remain unknown, the question of whether forms are authorial or scribal is best determined from an analysis of the distribution of the forms. Benson’s (1992) analysis of Chaucer’s spelling does address the question of distribution, but the data upon which his analysis is constructed is flawed by a number of serious inaccuracies and problematic assumptions (see Horobin 1998). In my own work on Chaucer’s spelling I have attempted to demonstrate a methodology which examines the distribution of spelling forms across the entirety of both the Hg and El manuscripts in order to determine whether a spelling is likely to be scribal or authorial. In order to demonstrate this methodology I used the word again(st) as a model for this example, as Samuels’ selection of the spelling agayn as Chaucerian has been regarded as authoritative.[5] What follows is a summary of the argument which I set out in full in my article ‘A New Approach to Chaucer’s Spelling’ (1998).

In his work on Hg and El Scribe B employed five alternative spellings for again(st): again, agayn, ageyn, ayein and ayeyn. In the following discussion I concentrate on the variation between the <g> and <y> graphemes: the variation between ai, ay, ei, ey is not considered as these diphthongs seem to be interchangeable. The <ag-> spelling is clearly the most common form throughout the entire text of both manuscripts, although the use of ayein/ayeyn is found alongside this spelling, concentrated in certain portions of text. There are 9 and 11 uses of the form <ay-> in Hg and El respectively, all clustered in restricted textual segments with remarkable correlation. Here are the line references:

| Hengwrt | Ellesmere | |

| Fragment I | ||

| KN | 34 [I. 892] | 34 |

| 651 [I. 1509] | 651 | |

| 929 [I. 1787] | ||

| L1 [MiP] | [Hg out] | 46/1 [I. 3155] |

| RE | 146 [I. 4067] | |

| CO | 16 [I. 4380] | |

| Fragment IV | ||

| CL | 320 [IV. 4320] | 320 |

| ME | 1016 [IV. 2260] | 1016 |

| 1069 [IV. 2313] | ||

| Fragment V | ||

| 88 [V. 96] | ||

| 119 [V. 127] | ||

| 662 [V. 670] | 662 | |

| Fragment VII | ||

| TM | 664 [VII. 1236] | |

| NP | 590 [VII. 3409] | |

| Fragment X | ||

| PA | 375 [X. 448] |

Such close correlation cannot reasonably be explained as the result of accidental transcription by a scribe transforming the spellings of his exemplar with the ‘practised ease and consistency’ Samuels assumed. The clustering of these forms in Hg alone warns against such a hypothesis, while the close agreement with the positioning of these spellings in El allows us to dismiss such a theory. The most likely explanation is that the use of these spellings reflects a change in usage in a common exemplar for these tales, or a change of the exemplar itself, preserved by direct scribal transcription. The differences that do remain in the exact uses of <ag-> and <ay-> forms in these tales may either be the result of an intermediate stage of copying of the common exemplar, or the mixed transcription and translation policy adopted by this scribe. Benson has also demonstrated a close correlation between the spellings ayein/ayeyn in the Hg and El manuscripts, and he used the evidence of Gg to reinforce his claim that such forms are archetypal, and therefore authorial. However his conclusions are undermined by the initial assumptions he adopted and the incorrect data upon which he based his interpretation. While Gg does not support the evidence drawn from Hg and El, significant conclusions can be drawn from the two manuscripts copied by Scribe D: Corpus Christi College, Oxford 198 and BL Harley 7334. Each manuscript has just two examples of spellings of again(st) which adopt the form <ay-> throughout the entire text, and their positioning shows startling consistency. The form ayayn appears at line 799 of TM [VII. 1769] in both manuscripts, while ayein is found at line 322 of SQ [V. 330] in Corpus 198 and line 584/1 of SQ [an extra line added after X. 592] in Harley 7334. The preservation of these four closely related spellings cannot be accidental, and must argue for the existence of these forms at these positions in their exemplars. The preservation of these spellings is especially marked given the strong West Midlands dialectal layer that their exemplars had passed through.[6] A further piece of supporting evidence comes from the distribution of these spellings in a later manuscript, although one whose text has close affiliations with Hg: BL Additional 35286. The Additional 35286 scribe uses the <ay-> spelling just 15 times, and the distribution reaffirms the findings discussed above. All uses are grouped within the following tales, with 4 agreements with the exact line reference in Hg, El or both: KN, L1, MI, RE, CL, ME, SQ, PR, SH, TM, PA. This evidence is also compelling for the survival of these forms despite the influence of the incipient Chancery Standard, the influence of which is common in the Additional 35286 language.[7] When we look beyond the evidence of the earliest manuscripts to a slightly later generation of copying, we see the almost total removal of the <ay-> spellings. This is demonstrated in the complete lack of such forms in both CUL Dd 4.24, the head of the a tradition, and BL Lansdowne 851, a c manuscript whose exemplar was close to that of Corpus 198.

Thus the spellings of again(st) using the form <ay-> display a consistency among the earliest and most authoritative Canterbury Tales manuscripts. As we move further from the archetype the <ay-> spellings are completely removed across different textual traditions. That the presence of the <ay-> spellings in these five authoritative manuscripts could be due to coincidental scribal error or conflation seems highly unlikely, and we must surely assume that they are the result of one ultimate common exemplar. Thus by close analysis of the distribution of individual spelling forms in this manner we are able to deduce the degree of transcription and translation carried out by individual scribes in their work on specific manuscripts. Where the direct preservation of exemplar spellings is clear we are able to compile a profile of spellings that derive from the common archetype. Where such manuscripts are known to be of high textual authority, this archetype will be close to the authorial holograph and thus significant for an assessment of the author’s own spelling habits. The evidence presented above suggests that the spelling ayein/ayeyn represents at least part of Chaucer’s own usage, thus contradicting Samuels’s conclusions and the argument that the Equatorie is in Chaucer’s own spelling system. However we must always remember that an ultimate common archetype may be at least one stage removed from that of the author, and any reconstruction of Chaucer’s own spelling practice remains speculative.

4. The Northernisms in the Reeve’s Tale

In this final section I will consider how the differences in the treatment of language in Hengwrt and Ellesmere affect the quality of the texts of the Canterbury Tales that they transmit. In order to assess this I will examine the treatment of Chaucer’s representation of Northern dialect in the dialogue of the students in the Reeve’s Tale. It has been noted by scholars that there are more Northernisms in the Ellesmere manuscript than in Hengwrt (for example, Burnley 1983, 116). Tolkien’s seminal discussion of the use of dialect in the Reeve’s Tale is based upon the text of El, and the assumption that El best preserves Chaucer’s own text of the dialect forms (Tolkien, 1934). However the differences between the El and Hg texts of the Northernisms reveals important evidence concerning the nature of linguistic editing that the El text has undergone.

Study of the representation of Northern dialect in the Hg manuscript reveals a number of inconsistencies in the realisation of Northern features in the speech of the undergraduates. For instance the reflex of Old English [OE] a which remained unrounded much longer in the North is generally written <a> in the students’ speech, eg. bathe, swa, banes. However there are several examples of spellings with the Southern rounded vowel <o> in this position, eg. bothe, none, told. In addition to these forms there is another spelling which appears to show OE a reflected in <ee>, heem HOME. This form and the related spellings geen and neen in El have been the cause of some confusion for philologists as they show an apparently unhistorical reflection of OE a in <ee>. These forms occur only in the Hengwrt [Hg] and Ellesmere [El] manuscripts of the Canterbury Tales, with the following distribution: heem HOME [Hg. RE 111; I. 4032]; geen GONE [El. RE 157; I. 4078]; neen NONE [El. RE 264, 266; I. 4185, 4187]. Tolkien was unable to account for such forms and he dismissed them as ‘ghostly’, speculating that they may be the result of scribal confusion between the <o> and <e> graphs (1934, 65-70). Subsequent studies have generally grouped these forms among other Northernisms with no attempt to account for their appearance.[8] Jeremy Smith (1995) has argued that these spellings may be explained as attempts to adapt a Southern orthography to represent changes in the realisation of long vowels in Northern dialects following the Great Vowel Shift.

However I have recently argued that the spelling heem does not represent an unhistorical reflection of OE ham but rather a straightforward development of Old Norse [ON] heim (Horobin 2000). The suggestion of an ON rather than an OE origin is of course appropriate for the representation of the Northern dialect, and the students’ dialogue contains a large amount of ON vocabulary, eg. hayl [RE 101; I. 4022] (ON heill), ille [RE 124; I. 4045] (ON illr), ymel [RE 250; I. 4171] (ON ímilli). This explanation cannot account for the appearance of the forms neen and geen in El, as such forms are not recorded in Old Norse. However these forms may be understood according to the editorial process which the El text has undergone. A number of differences between the Hg and El texts of the Reeve’s Tale reveal attempts by the El scribe or editor to increase the representation of Northern dialect, and to regularise the inconsistencies found in Hg (see further Smith 1995). For instance Hg’s sole use of slyk (ON slíkr) at line RE 249 [I. 4170] alongside the usual Northern ME form swilk, is found in three further occurrences in El [lines RE 209, I. 4130 (2); RE 249, I. 4173]. A similar tendency towards increasing and regularising the Hg usage might therefore explain the appearance of the forms geen and neen. It seems that in copying El the scribe or editor viewed the form heem as showing a specifically Northern reflex of OE ham and transferred this same development to the related forms nan and gan. It seems that in copying El the scribe or editor was attempting to emend the spelling of his copytext according to a system that he did not fully understand. This is well exemplified by a comparison of the treatment of adjectival final <-e> in line A 4175 in the Hg and El manuscripts. In Hg this line reads: This lang nyght ther tydes me na reste, while El has the weak form of the adjective: This lange nyght ther tydes me na reste. While the El reading is grammatically correct according to Chaucer’s own practice, it fails to notice that the uninflected form is appropriate to the Northern dialect of the students, following the much earlier loss of the distinction between weak and strong adjectives in the North of England. This example shows the scribe applying a grammatical principle to an environment where it was not appropriate, in a similar way as I have suggested for the spellings geen and neen. These readings suggest that while the El scribe or editor emended the language of his copytext intelligently, he was not always fully aware of the linguistic subtleties of Chaucer’s text.

5. Conclusions

The language of the Hg manuscript is closely related to that of El, copied by the same scribe, and other manuscripts written in London circa 1400. However Hg shows a greater degree of variation than El: variation which appears to derive from the copytext and possibly from the authorial holograph. As such the Hg manuscript best preserves elements of Chaucer’s own spelling practices, while the El manuscript shows evidence of careful linguistic editing and regularisation. The variation found in Hg, which derives from Chaucer’s own spelling practices, shows the overlap between different types of London English, and suggests the gradual process by which Type II became replaced by Type III. The removal of the few older theigh spellings of THOUGH, and the attempts to increase the Northern dialect forms in the Reeve’s Tale, demonstrate attempts by the El scribe or supervisor to present a more regular and consistent text. These conclusions have implications for the editing of the Canterbury Tales, suggesting that the Hg manuscript is the best evidence we have for Chaucer’s language and that editors must be cautious in their use of the evidence of the El manuscript.

Bibliography

Benskin, Michael, and Margaret Laing. “Translations and Mischsprachen in Middle English Manuscripts.” In So Meny People Longages and Tonges: Philological Essays in Scots and Medieval English presented to Angus McIntosh. Ed. M. Benskin and M. L. Samuels. Edinburgh: Edinburgh Middle English Dialect Project, 1981. 55-106.

Benson, Larry D., ed. The Riverside Chaucer. 3rd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987.

Benson, Larry D. “Chaucer’s Spelling Reconsidered.” English Manuscript Studies 1100-1700 3 (1992): 1-28. Rpt in Contradictions: From Beowulf to Chaucer. Eds T. M. Andersson and S. A. Barney. Aldershot, 1995.

Burnley, D. The Language of Chaucer. London, 1983.

Burrow, J. A. Thomas Hoccleve’s Complaint and Dialogue. EETS o.s. 313. Oxford, 1999

Doyle, A. I., and M. B. Parkes. “The Production of Copies of the Canterbury Tales and the Confessio Amantis in the Early Fifteenth Century.” In Medieval Scribes, Manuscripts, and Libraries: Essays Presented to N. R. Ker. Ed. M. B. Parkes and A. G. Watson. London: Scolar Press, 1978. 163-210.

Furnivall, Frederick J., and I. Gollanz, eds. Hoccleve’s Works. EETS e.s., 61 and 73. London: Oxford UP, 1892 and 1925. Rev. ed. Jerome Mitchell and A. I. Doyle, 1970.

Horobin, Simon. “Additional 35286 and the Order of the Canterbury Tales.” Chaucer Review 31 (1997): 272-8.

Horobin, Simon. A Transcription and Study of British Library MS Additional 35286. PhD. Dissertation. Sheffield, 1997.

Horobin, Simon. “A New Approach to Chaucer’s Spelling.” English Studies 79 (1998): 415-24.

Horobin, Simon. “Some Spellings in Chaucer’s Reeve’s Tale.” Notes and Queries n.s. 47 (2000): 16-18

Horobin, Simon. “Chaucer’s Spelling and the Manuscripts of the Canterbury Tales.” In Placing Middle English in Context. In Irma Taavitsainen et al. (forthcoming)

Robinson, Pamela. “Geoffrey Chaucer and the Equatorie of the Planetis: The State of the Problem” Chaucer Review 26 (1991): 17-30.

Samuels, M. L. “Some Applications of Middle English Dialectology” English Studies 64 (1963). Rpt. in Middle English Dialectology: Essays on Some Principles and Problems. Ed. Margaret Laing. Aberdeen: University of Aberdeen Press, 1989. 64-80.

Samuels, M. L., and J. J. Smith. “The Language of Gower.” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 82 (1981): 295-304. Rpt. in The English of Chaucer and his Contemporaries: Essays by M. L. Samuels and J. J. Smith. Ed. J. J. Smith. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1988. 13-22.

Samuels, M. L. “The Scribe of the Hengwrt and Ellesmere MSS.” In The English of Chaucer and his Contemporaries: Essays by M. L. Samuels and J. J. Smith. Ed. J. J. Smith. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1988. 38-50.

Samuels, M. L. “Spelling and Dialect in the Late and Post-Middle English Periods.” In The English of Chaucer and his Contemporaries: Essays by M. L. Samuels and J. J. Smith. Ed. J. J. Smith. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1988. 86-95.

Smith, Jeremy J. “The Trinity Gower D-Scribe and his Work on Two Early Canterbury Tales MSS.” In The English of Chaucer and his Contemporaries. Ed. J. J. Smith. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1988. 51-69.

Smith, Jeremy J. “The Language of the Ellesmere Manuscript.” In The Ellesmere Chaucer: Essays in Interpretation. Ed. Martin Stevens and Daniel Woodward. San Marino, CA & Tokyo: Huntington Library & Yushodo Co., Ltd., 1995. 69-86.

Smith, Jeremy J. “The Great Vowel Shift in the North of England and some forms in Chaucer’s Reeve’s Tale.” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen. 94 (1995): 433-37.

Smith, Jeremy J. An Historical Study of English: Function, Form and Change. London, 1996.

Tolkien, J. R. R. “Chaucer as a Philologist: The Reeve’s Tale.” Transactions of the Philological Society 1934. 1-70.

Notes

| 1. | For a discussion of the significance of the spelling ‘theigh’ and its appearance in later manuscripts of the Canterbury Tales see Horobin ‘Chaucer’s Spelling and the Manuscripts of the Canterbury Tales.’ (forthcoming) |

| 2. | For texts contained in the Hoccleve holograph manuscripts see Furnivall 1970 and Burrow 1999. |

| 3. | These manuscripts are Bodleian Library Fairfax 3 and Huntington Library El 26 A 17. For the argument that these manuscripts preserve Gower’s own spelling habits and are ‘in all respects except their actual handwriting, as good as autograph copies’ see Samuels and Smith 1998. |

| 4. | For the term ‘constrained selection’ and a comprehensive discussion of the different types of scribal behaviour see Benskin and Laing 1981. |

| 5. | P. Robinson 1991 used the consistent appearance of the ‘highly idiosyncratic’ Chaucerian spelling ‘agayn(s)’ in the Equatorie of the Planetis as conclusive proof that ‘Peterhouse 75.I is Geoffrey Chaucer’s holograph’. |

| 6. | For a detailed analysis of the dialectal layers in the language of Scribe D, see J. J. Smith, ‘The Trinity Gower D-Scribe’ (1988). |

| 7. | For an analysis of the language of BL Additional 35286 see Horobin 1997, chapter 6. |

| 8. | For example, the notes in the Riverside Chaucer simply mark geen and neen as (Nth). |